Emir Šehanović

- Works

- Exhibitions

- Fairs

- Editions/Books

-

News

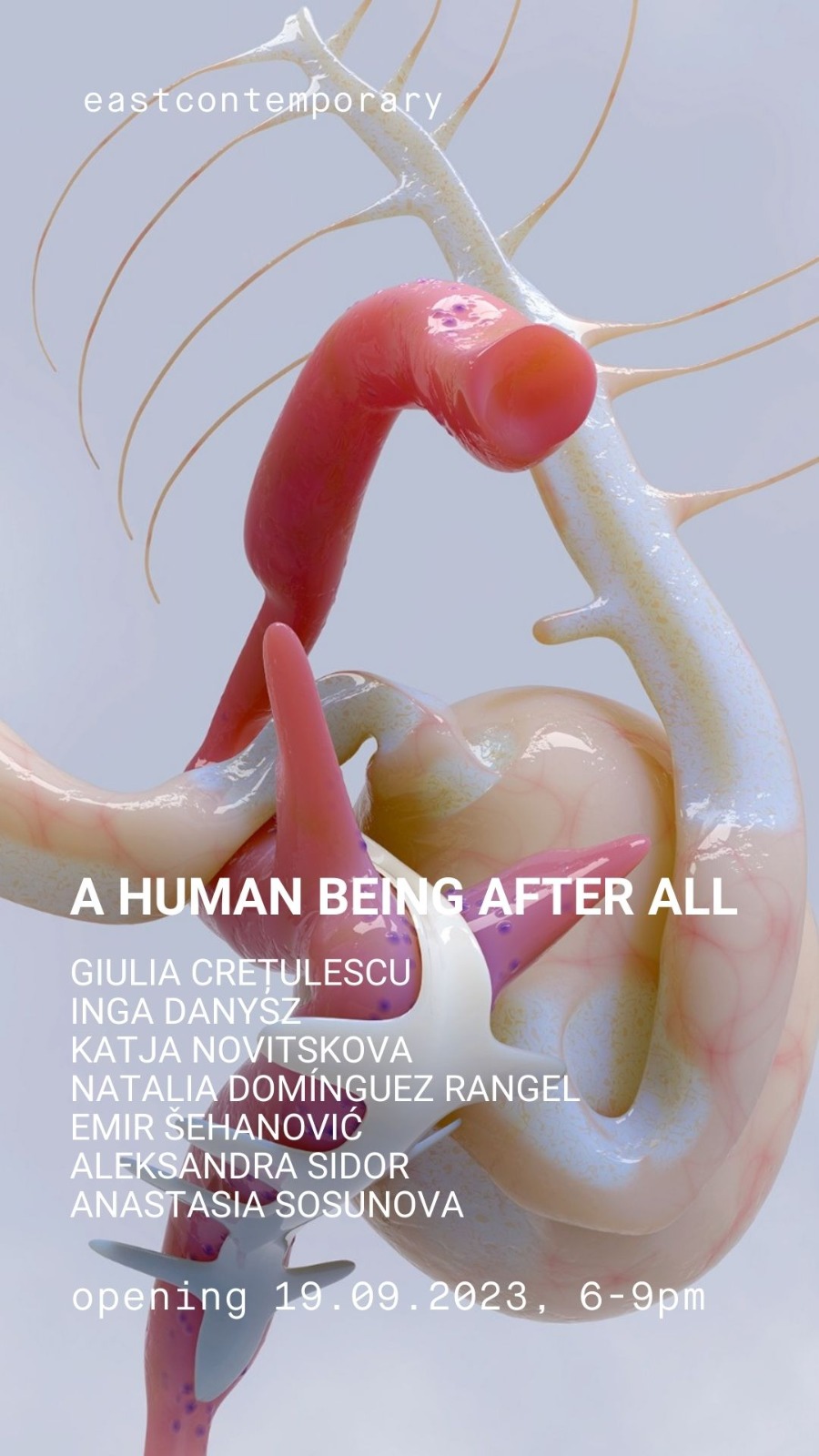

EMIR ŠEHANOVIĆ – A HUMAN BEING AFTER ALL

- Inquire about the artist

- Back to artists

‘A human being after all’ is a group exhibition that evolves into a sensorial journey, where subjects and matters gently linger in a constant state of transformation. Through a series of sculptures, paintings and installations oscillating on the verge of alienation and intimacy, the artists shape an uncanny, yet fascinating vision of a new world permeated with fluid and carnal desire for interconnectedness among different bodies.

eastcontemporary, via Giuseppe Pecchio 3, Milan

Giulia Crețulescu, Inga Danysz, Katja Novitskova, Natalia Domínguez Rangel, Emir Šehanović, Aleksandra Sidor, Anastasia Sosunova

19/09 – 17/11/2023

The history of human beings is a “techno-heroic” history of violence, death, and oppression of other species (animals and plants). It is an history of conquest, looting, and depletion of the planet’s resources. Let’s take any of the textbooks we study in our schools and we will realise that human history is cyclically marked by armed conflicts, ruthless revenge and bloody wars that have poisoned humankind by wiping out entire populations. It is inevitable, humans are seduced by their own extinction, and that of others. They ontologically practice self-destruction, they are self harmers, inclined to evil against themselves and everything around them. For them, the end is not so much imminent, chronologically close, but rather rooted in their essence and constitutive of their being. In a word: immanent. The life of human beings is glorious, while their death is meaningful.

At least, this is the vulgata, the story that humanity has told itself for quite some time, and still persists in our imagination today, also thanks to the contribution of arts such as cinema and literature. Think of the famous scene, sanctified in cinema history, from 2001: A Space Odyssey, in which the ape-man, our primordial archetype, understands at some point that he can use the bone of an animal carcass as a war tool to procure food and subdue other species. While Richard Strauss’s epic symphony is playing in the background, a primitive gesture – pointing the bone of an animal skeleton to the sky – turns into a hymn to discovery and ascent. Although the genus Homo will not make its appearance on the planet until 2 million years later, it is at that precise moment, that is, when the hominid creates an object with a specific function through the techné, that the fratricidal history of humanity begins.

What if we tried to tell another history instead? The history of non-killers, non-colonizers, non-masters, non-heroes… In the 1970s, the American anthropologist Elizabeth Fisher spread a curious evolutionary theory called “Carrier Bag Theory”. According to Fisher, the cultural device used by the first humans on Earth was not, as the contemporary theories claimed, a hunting tool – a spear or a stick – but rather a container, a tool designed to collect food and transport it home, a tool for care.

A decade later, Ursula Le Guin would take up Fisher’s “Carrier Bag Theory” and incorporate it into her theory of the novel and fiction. In her essay, The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, published in 1988, she will apply the metaphor of the container that needs to be filled (with words, concepts, images) to the science fiction novel. In this way literature finally begins to tell the anti-heroic history of human beings. As a matter of fact, accepting the idea that human history is full of objects used for hitting, wounding and killing means accepting only one of the many histories that can be told. And today more than ever, contemporary arts, which embrace horizontally different media by dialoguing with multiple disciplines, may be able to imagine alternatives and counter-narratives not only of our most distant past, but above all of our imminent and uncertain future over which hovers the spectar of the Anthropocene.

“A human being after all” brings out clearly the intersection of this dual temporality in tension between past and future. The exhibition brings together a series of sculptures, paintings and installations that make up the alternative imagery of our evolutionary history. Within the aseptic space of the white cube, a series of objects testifies to a sudden change of course in the broader evolutionary path of the human species. By looking at some of the objects in the exhibition, it is as if the protagonists of this history, which our tradition would like to be progressive and linear, suddenly decided to take another path, a parallel path among the many still viable ones.

As for Katja Novitskova’s Earthware (dreaming of a purple simian), it is impossible not to suggest a reference to Kubrick’s famous film scene. The painting, made by transferring the image of a computer-generated monkey onto a synthetic clay tablet, stands as the last fossil record of an extinct population or, as the title suggests, produced by the dreamlike imagination. It is difficult not to see in this humanity a reference to a purely feminine dimension: after all, purple is the colour of feminist claims and historically represents the struggle for gender equality.

In the other works, the element of corporeality takes on a central importance in defining this new humanity that faces the future through a rewriting of its past. Giving centrality to the body means placing emphasis on the process through which human subjects co-constitute themselves. The body, in fact, does not represent a mere biological information about the subject, but the device from which the human being, immersed in a specific environment, subjectifies himself through the embodied experience of reality.

In these works, the body is central: this is the case, for example, of Partly (2023), a painting by Aleksandra Sidor in which a lyrical and in some respects surrealist visual language and a voyeuristic focus on a nonconforming and at times grotesque corporeality converge. However, the lens with which the artist observes and reconstructs these deformed body parts reflects, more than a pure anatomical interest, a desire to delve into the psychic and emotional unconscious, returning restless and turbulent images to the viewer.

The body is also present in Emir Šehanović’s Unknown Quantity 4 (2020), a photograph that reproduces a twisted organic shape with an alien physiognomy. Entirely made digitally, the image of this posthuman relic reveals a condition of precariousness and fragility, as if to testify to the inexorable failure of the species that produced it. On the other hand, Anastasia Sosunova leads an exercise in body deconstruction. She is an artist who explores gender and queer issues in her work. Costume For a Flying Rock (they say it nearly broke the window) (2022) is a sculpture in copper, plastic and steel that frames the print of a transgender anthropomorphic figure in which male and female elements converge. This figure holds a stone, guarded in a layer of resin placed at the foot of the structure: it is a stone thrown at the parliament of Vilnius in occasion of an LGBTQ+ event and collected by the artist.

Finally, a corporeality in presence is also found in Female orgasm (2021) by Natalia Dominguez Rangel, a glass sculpture born from a mistake made during the manufacturing process and which reflects on the relationship between nature and artifice. Focusing on the acoustic frequencies reproduced by the human body, the work stimulates a parallelism between the process of transformation from solid to liquid of a fragile material such as glass, which requires immediacy of execution, and female orgasm.

But, within the exhibition, the theme of the body is central even in its absence: this is instead the case of Fascia anterioris (2023) by Giulia Crețulescu, an object stripped of the body it is supposed to accommodate, and therefore deprived of any immediate function. Perhaps picking up Anna Uddenberg’s aesthetical legacy, the artist transforms a potential prosthetic element capable of increasing body architecture into a disturbing totemic and fetishistic object to be limited to observing, an ergonomic harness ready to house a body that has yet to be built.

The absence of the body becomes deafening, and therefore central, also in the totemic work by Inga Danysz. Sarcophagus 03 (2022) is a life-size minimalist sculpture obtained through a work of subtraction. Stripped of any ornamental motif, the sarcophagus, by not revealing its recipient, gives to the exhibition space an aura of solemn gravity. And here comes the image of the carrier bag, the empty instrument to be filled, in which the ostensible motif of the funeral ritual is depowered by depriving the instrument of its original magical-protective function of facilitating the survival of the deceased in the afterlife. The aluminum and steel sarcophagus appears to us rather as a work of design, a symbolic presence, an anonymous memento mori generalised to all humankind.

One of the main political functions of art is this: to deconstruct, in a critical way, the institutional knowledge on which the oppressive systems of our current society are based, and to disseminate, through the very powerful weapon of imagination, new visions and new imaginaries of being in the world and of (co)existing.

Starting from these premises, “A human being after all” tells not a history of hunters, warriors or murdering heroes, nor a history written by ruthless winners. Indeed, the history of human beings can also be a history made of precarious objects and subjects, with undefined contours, a history that, instead of reflecting heroic victories, reproduces our weaknesses, mistakes and constant failures, because – as Jack Halberstam says – “living means failing, messing up, disappointing and, in the end, dying”. It’s the history of human beings, another history we can choose to tell.

Dario Ali

The exhibition was organized with the support of General Consulate of Poland in Milan and Polish Institute in Rome.